Choosing the research question

Whose responsibility is it?

Whose responsibility is it?

The key to the Individual Scientific Investigation is the research question. Without a good research question you will be unable to address the internal assessment criteria effectively. The IB states clearly that the formulation of the research question for the Individual Scientific Investigation is the student’s responsibility. Although teachers may suggest possible topics and approaches to formulating questions they cannot allocate specific research questions to study. Your teacher is expected to guide you to ensure that your research question is commensurate with the level of the course and is compatible with the assessment criteria. They should also check that it is safe to carry out if it involves practical work and that it complies with the IB's ethical guidelines.

What you need to know in order to choose a good research question

As you work through your practical work during your first year and scaffold your way towards your individual investigation you will need to know:

1. When you eventually do the Internal Assessment you will be required to come up with an investigation that matches the assessment criteria. This effectively means that:

- it should show personal significance, interest or curiosity.

- the research question can be clearly described

- it will produce sufficient relevant quantitative and qualitative raw data to support a detailed and valid conclusion.

2. The investigation can take many forms. It can include, for example:

- a practical laboratory investigation

- use of a spreadsheet to analyse and model

- extraction of data from a database and then analysing it graphically

- combination of spreadsheet/database work with a practical laboratory investigation

- use of an interactive and open-ended simulation

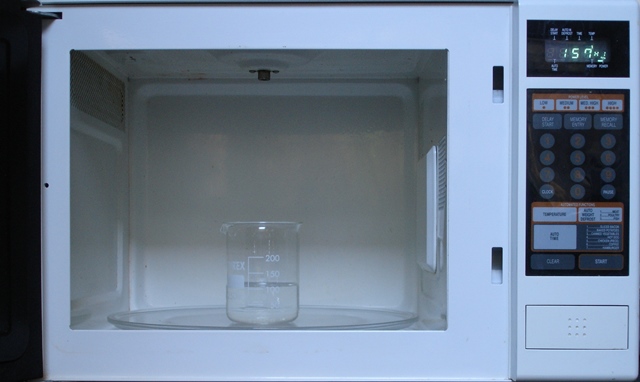

As you learn the necessary skills through the practical scheme of work discuss with your teacher how each practical might be used to provide the basis for an investigation. Consider unresolved questions and/or ways in which the techniques could be altered or extended to cover other possible areas to explore. For example, when calculating ΔH⦵ for the redox reaction between zinc and copper(II) sulfate it is usual to assume that the solution has the same specific heat capacity as pure water. How valid is this assumption? You could investigate this by using an ordinary household microwave oven. If you pass the same amount of energy through the same mass of solutions containing different concentrations of a salt (independent variable) and measure the temperature rise (dependent variable) you could then determine whether the specific heat capacity changes. This example also illustrates that many of the best investigations can be done relatively quickly using simple apparatus.

A microwave oven provides a simple, quick and efficient way to perform experiments

on the polarity of molecules and on specific heat capacities.

‘Hands on’ or ‘hands off’?

1. ‘Hands on’

If you chooses to do traditional practical work then it may be worth looking at the techniques that are readily available in a school laboratory and considering examples of topics that could be investigated using each technique. I have in fact already made a list on page 179 of my Study Guide, as this is an approach sometimes used for Extended Essays. Some typical techniques (or equipment that could be used) include:

Titration – acid-base and redox

Extension or refinement of a standard practical

Chromatography

Calorimetry

Use of a pH meter

Electrolysis

Voltaic cells

Microwave oven

Polarimeter

Data logging probes

Visible spectrometer (or colorimeter)

Gravimetric analysis

Microscale

Note that some of these could be used at home using simple apparatus and chemicals that could be bought in local shops. For an example see James Midgley's video ![]() How do to chemistry with your iphone.

How do to chemistry with your iphone.

2. ‘Hands off’

This may seem an easier option but may in fact be more difficult as it is harder (but not impossible) to show personal engagement. If you choose this route you should probably try to find your secondary data from a variety of sources (rather than a single source) and then process it in a way that has not been done before. For example, you should have learned that you should compare the values you obtain in your own experiments with the literature values. You are encouraged to give your own values together with the degree of uncertainty and yet when you look in the data book no uncertainties are given. If you look in a different data book often a different 'literature value' is quoted also with no associated uncertainty – so which is the ‘true’ value and how accurate is it? An interesting investigation might be to compare values from different data sources (see Measuring energy changes for an example) to determine how reliable ‘the literature values’ actually are.

3. ‘Hands on and off’

Possibly the most satisfying investigations are those that combine primary data generated by you with secondary data that you have researched from elsewhere. For example, you might determine the percentage of copper in a coin and then research the literature to find how the percentage has changed over the years as the price of copper has fluctuated.

IB Docs (2) Team

IB Docs (2) Team